Radiación adaptativa: Diferenzas entre revisións

| Liña 31: | Liña 31: | ||

=== Innovación === |

=== Innovación === |

||

| ⚫ | |||

A evolución dunha característica nova pode permitir que un clado se diversifique ao facer accesibles novas áreas de morfoespazo. Un exemplo clásico é a evolución da cuarta cúspide nos dentes de mamífero. Ese trzazo permite un gran incremento nos tipos de alimentos que poden comer. A evolución deste carácter incrementou o número de [[nicho ecolóxico|nichos ecolóxicos]] dispoñibles para os mamíferos. O trazo orixinouse varias veces en diferentes grupos durante o [[Cenozoico]], e en cada caso foi seguido inmediatamente por unha radiación adaptativa.<ref name=Jernvall1996>{{Cite journal | first1 = J. | last1 = Jernvall | first2 = J. P. | last2 = Hunter | first3 = M. | last3 = Fortelius |

|||

| title = Molar Tooth Diversity, Disparity, and Ecology in Cenozoic Ungulate Radiations |

| title = Molar Tooth Diversity, Disparity, and Ecology in Cenozoic Ungulate Radiations |

||

| journal = Science |

| journal = Science |

||

| Liña 41: | Liña 41: | ||

| pmid = 8929401 |

| pmid = 8929401 |

||

| doi = 10.1126/science.274.5292.1489 |

| doi = 10.1126/science.274.5292.1489 |

||

|bibcode = 1996Sci...274.1489J}}</ref> |

|bibcode = 1996Sci...274.1489J}}</ref> Nas aves a evolución do voo abriulles novos camiños para a súa [[evolución]], iniciando unha radiación adaptativa.<ref>{{cite book |

||

| title = The Origin and Evolution of Birds |

| title = The Origin and Evolution of Birds |

||

| first = Alan | last = Feduccia | year = 1999 |

| first = Alan | last = Feduccia | year = 1999 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

Outros exemplos inclúen a [[xestación]] dos [[placentarios]] (nos mamíferos [[euterios]]), ou o [[bipedismo]] (nos [[homininos]]).<ref name="Levin-21" /> |

|||

=== Oportunidade === |

=== Oportunidade === |

||

Adaptive radiations often occur as a result of an organism arising in an environment with unoccupied niches, such as a newly formed lake or isolated island chain. The colonizing population may diversify rapidly taking advantage of all possible niches. |

|||

As radiacións adaptativas adoitan ocorrer como resultado da orixe dun organismo nun ambiente con nichos non ocupados, como os lagos de nova formación ou unha cadea de illas. A poboación colonizada pode diversificarse rapidamente tomando vbantaxe de todos os nichos posibles. |

|||

In [[Lake Victoria]], an isolated lake which formed recently in the African rift valley, over 300 species of [[cichlid]] fish adaptively radiated from one parent species in just 15,000 years. |

|||

Cando se formou o [[lago Vitoria]] como un lago illado no [[val do rift]] africano, unhas 300 especies de peixeds [[cíclidos]] radiaron adaptativaamente desdde unha especie parental e só 15.000 anos. |

|||

Adaptive radiations commonly follow [[mass extinction]]s: following an extinction, many niches are left vacant. A classic example of this is the replacement of the non-avian dinosaurs with mammals at the [[Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event|end of the Cretaceous]]. |

|||

As radiacións adaptativas danse despois de [[extinción en masa|extincións en masa]]: despois dunha extinción, quedan vacantes moitos nichos. Un exemplo clásico disto é a substitución dos [[dinosauro]]s non aviarios polos mamíferos ao [[evento de extinción Cretáceo–Paleoxeno|final do Cretáceo]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

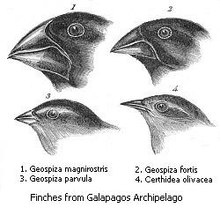

=== Pimpíns de Darwin === |

=== Pimpíns de Darwin === |

||

One famous example where adaptive radiation is seen is with [[Darwin's finches]]. It has been observed by many evolutionary biologists that fragmented landscapes oftentimes are a prime location for adaptive radiation to occur. The differences in geography throughout disjointed landscapes such as islands are believed to promote such diversification. Darwin's finches occupy the fragmented landscape of the [[Galápagos Islands]] and are diversified into many different species which differ in ecology, song, and morphology, specifically the size and shapes of their [[beak]]s. The first obvious explanation for these differences is [[allopatric speciation]], speciation that occurs when populations of the same species become isolated geographically and evolve separately. Because the finches are divided amongst the islands, the birds have been evolving separately for several million years. However, this does not account for the fact that many of the species occur in [[sympatry]], with seven or more species inhabiting the same island.<ref name="Petren, K. 2005">{{cite journal | last1 = Petren | first1 = K. | last2 = Grant | first2 = P. R. | last3 = Grant | first3 = B. R. | last4 = Keller | first4 = L. F. | year = 2005 | title = Comparative landscape genetics and the adaptive radiation of Darwin's finches: the role of peripheral isolation | url = | journal = Molecular Ecology | volume = 14 | issue = 10| pages = 2943–2957 | doi=10.1111/j.1365-294x.2005.02632.x}}</ref> This raises the question as to why these species split when living in the same environment with all the same resources. Petren, Grant, Grant, and Keller proposed that the speciation of the finches occurred in two parts: an initial, easily observable allopatric event followed by a less clear sympatric event. This sympatric event which occurred second was adaptive radiation.<ref name="Petren, K. 2005"/> This occurred largely to promote specialization upon each island. One major morphological difference among species sharing one island is beak size and shape. Adaptive radiation led to the evolution of different beaks which could access different food and resources. Those with short beaks are better adapted to eating seeds on the ground, those with thin, sharp beaks eat insects, and those with long beaks use their beaks to probe for food inside cacti. With these specializations, seven or more species of finches are able to inhabit the same environments without competition or lack of resources killing several off. In other words, these morphological differences in beak size and shape brought about by adaptive radiation allow the island diversification to persist. |

One famous example where adaptive radiation is seen is with [[Darwin's finches]]. It has been observed by many evolutionary biologists that fragmented landscapes oftentimes are a prime location for adaptive radiation to occur. The differences in geography throughout disjointed landscapes such as islands are believed to promote such diversification. Darwin's finches occupy the fragmented landscape of the [[Galápagos Islands]] and are diversified into many different species which differ in ecology, song, and morphology, specifically the size and shapes of their [[beak]]s. The first obvious explanation for these differences is [[allopatric speciation]], speciation that occurs when populations of the same species become isolated geographically and evolve separately. Because the finches are divided amongst the islands, the birds have been evolving separately for several million years. However, this does not account for the fact that many of the species occur in [[sympatry]], with seven or more species inhabiting the same island.<ref name="Petren, K. 2005">{{cite journal | last1 = Petren | first1 = K. | last2 = Grant | first2 = P. R. | last3 = Grant | first3 = B. R. | last4 = Keller | first4 = L. F. | year = 2005 | title = Comparative landscape genetics and the adaptive radiation of Darwin's finches: the role of peripheral isolation | url = | journal = Molecular Ecology | volume = 14 | issue = 10| pages = 2943–2957 | doi=10.1111/j.1365-294x.2005.02632.x}}</ref> This raises the question as to why these species split when living in the same environment with all the same resources. Petren, Grant, Grant, and Keller proposed that the speciation of the finches occurred in two parts: an initial, easily observable allopatric event followed by a less clear sympatric event. This sympatric event which occurred second was adaptive radiation.<ref name="Petren, K. 2005"/> This occurred largely to promote specialization upon each island. One major morphological difference among species sharing one island is beak size and shape. Adaptive radiation led to the evolution of different beaks which could access different food and resources. Those with short beaks are better adapted to eating seeds on the ground, those with thin, sharp beaks eat insects, and those with long beaks use their beaks to probe for food inside cacti. With these specializations, seven or more species of finches are able to inhabit the same environments without competition or lack of resources killing several off. In other words, these morphological differences in beak size and shape brought about by adaptive radiation allow the island diversification to persist. |

||

Revisión como estaba o 10 de xullo de 2016 ás 23:08

Este artigo está a ser traducido ao galego por un usuario desta Wikipedia; por favor, non o edite. O usuario Miguelferig (conversa · contribucións) realizou a última edición na páxina hai 7 anos. Se o usuario non publica a tradución nun prazo de trinta días, procederase ó seu borrado rápido. |

En bioloxía evolutiva, unha radiación adaptativa é un proceso no cal os organismos diversifícanse rapidamente a partir dunha especie ancestralnunha multitude de novas formas, especialmente cando o cambio no ambiente fai que queden dispoñibles novos recursos, creando novos retos, ou abrindo novos nichos.[1][2] Empezando cun só antepasado común, este proceso dá lugar a unha especiación e a adaptación fenotípica nun conxunto d e especies que mostran trazos morfolóxicos e fisiolóxicos diferentes cos cales poden explotar un abano de ambientes diverxentes.[2]

A radiación adaptativa, un xemplo característrico de cladoxénese, pode ser ilustrada graficamente como un "arbusto", ou clado, de especies que coexisten (na árbore da vida). [3] Os lagartos anolinos do Caribe son un exemplo particularmente interesante dunha radiación adaptativa.[4] As illas Hawai son un arquipélago moi illado e nel se encontran moitos exemplos de radiación adaptativa. Un exemplo excepcional de radiación adaptativa é o das especies de aves do xénero Cyanerpes hawaianas. Por medio da selección natural, estes paxaros adaptáronse rapidamente e converxeron segundo os dferentes ambientes das illas hawaianas nos que vivían.[5]

Realizáronse moitas investigacións sobre a radiación adaptativa debido aos seus drásticos efectos na diversidade da poboación. Porén, cómpre facer máis investigación, especialmente para comprender completamente os moitos factores que afectan á radiación adaptativa. Os enfoques empíricos e teóricos son ambos útiles, aínda que cada un ten as súas desvantaxes.[6]

Identificación

Poden usarse catro características para identificar unha radiación adaptativa, que son:[2]

- Un antepasado común das especies compoñentes: especificamente un antepasado recente. Nótese que isto non é o mesmo que unha monofilia, na cal están incluídos todos os descendentes dun antepasado común.

- Unha correlación fenotipo-ambiente: unha asociación significativa entre ambientes e os trazos morfolóxicos e fisiolóxicos usados para explotar eses ambientes.

- Utilidade do trazo: as vantaxes de fitness dos valores do trazo nos seus correspondentes ambientes.

- Especiación rápida: presenza dunha ou máis explosións na emerxencia de novas especies no momento en que a diverxencia ecolóxica e fenotípica está comezando.

Causas

Innovación

A evolución dunha característica nova pode permitir que un clado se diversifique ao facer accesibles novas áreas de morfoespazo. Un exemplo clásico é a evolución da cuarta cúspide nos dentes de mamífero. Ese trzazo permite un gran incremento nos tipos de alimentos que poden comer. A evolución deste carácter incrementou o número de nichos ecolóxicos dispoñibles para os mamíferos. O trazo orixinouse varias veces en diferentes grupos durante o Cenozoico, e en cada caso foi seguido inmediatamente por unha radiación adaptativa.[7] Nas aves a evolución do voo abriulles novos camiños para a súa evolución, iniciando unha radiación adaptativa.[8] Outros exemplos inclúen a xestación dos placentarios (nos mamíferos euterios), ou o bipedismo (nos homininos).[3]

Oportunidade

As radiacións adaptativas adoitan ocorrer como resultado da orixe dun organismo nun ambiente con nichos non ocupados, como os lagos de nova formación ou unha cadea de illas. A poboación colonizada pode diversificarse rapidamente tomando vbantaxe de todos os nichos posibles.

Cando se formou o lago Vitoria como un lago illado no val do rift africano, unhas 300 especies de peixeds cíclidos radiaron adaptativaamente desdde unha especie parental e só 15.000 anos.

As radiacións adaptativas danse despois de extincións en masa: despois dunha extinción, quedan vacantes moitos nichos. Un exemplo clásico disto é a substitución dos dinosauros non aviarios polos mamíferos ao final do Cretáceo.

Exemplos

Notas

- ↑ Larsen, Clark S. (2011). Our Origins: Discovering Physical Anthropology (2 ed.). Norton. p. A11.

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 2,2 Schluter, Dolph (2000). The Ecology of Adaptive Radiation. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-19-850523-X.

- ↑ 3,0 3,1 Lewin, Roger (2005). Human evolution : an illustrated introduction (5th ed.). p. 21. ISBN 1-4051-0378-7.

- ↑ Parallel Adaptive Radiations - Caribbean Anoline Lizards. Tood Jackman. Villanova University. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ↑ Reding, DM; Foster, JT; James, HF; Pratt, D; Fleischer, RC (2009). "Convergent evolution of 'creepers' in the Hawaiian honeycreeper radiation". Biology Letters 5: 221–224. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0589.

- ↑ Gavrilets, S.; Losos, J. B. (2009). "Adaptive radiation: contrasting theory with data". Science 323 (5915): 732–737. doi:10.1126/science.1157966.

- ↑ Jernvall, J.; Hunter, J. P.; Fortelius, M. (1996). "Molar Tooth Diversity, Disparity, and Ecology in Cenozoic Ungulate Radiations". Science 274 (5292): 1489–1492. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1489J. PMID 8929401. doi:10.1126/science.274.5292.1489.

- ↑ Feduccia, Alan (1999). The Origin and Evolution of Birds.

Véxase tamén

Outros artigos

| Commons ten máis contidos multimedia sobre: Radiación adaptativa |

- Explosión cámbrica—a radiación adaptativa de máis sona

- Radiación evolutiva—un temo máis xeral para describir calquera radiación

Bibliografía

- Wilson, E. et al. Life on Earth, by Wilson, E.; Eisner, T.; Briggs, W.; Dickerson, R.; Metzenberg, R.; O'brien,R.; Susman, M.; Boggs, W.; (Sinauer Associates, Inc., Publishers, Stamford, Connecticut), c 1974. Chapters: The Multiplication of Species; Biogeography, pp 824–877. 40 Graphs, w species pictures, also Tables, Photos, etc. Includes Galápagos Islands, Hawaii, and Australia subcontinent, (plus St. Helena Island, etc.).

- Leakey, Richard. The Origin of Humankind—on adaptive radiation in biology and human evolution, pp. 28–32, 1994, Orion Publishing.

- Grant, P.R. 1999. The ecology and evolution of Darwin's Finches. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Mayr, Ernst. 2001. What evolution is. Basic Books, New York, NY.

- Kemp, A.C. (1978). "A review of the hornbills: biology and radiation". The Living Bird 17: 105–136.

- Gavrilets, S.; Vose, A. (2005). "Dynamic patterns of adaptive radiation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 18040–18045. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506330102.

- Gavrilets, S. and A. Vose. 2009. Dynamic patterns of adaptive radiation: evolution of mating preferences. In Butlin, RK, J Bridle, and D *Schluter (eds) Speciation and Patterns of Diversity, Cambridge University Press, page. 102–126.

- Baldwin, Bruce G.; Sanderson, Michael J. (1998). "Age and rate of diversification of the Hawaiian silversword alliance (Compositae)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95 (16): 9402–9406. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.16.9402.

- Gavrilets, S.; Losos, J. B. (2009). "Adaptive radiation: contrasting theory with data". Science 323 (5915): 732–737. doi:10.1126/science.1157966.

- Irschick, Duncan J.; et al. (1997). "A comparison of evolutionary radiations in mainland and Caribbean Anolis lizards". Ecology 78 (7): 2191–2203. doi:10.2307/2265955.

- Losos, Jonathan B (2010). "Adaptive Radiation, Ecological Opportunity, and Evolutionary Determinism". The American Naturalist 175 (6): 623–39. doi:10.1086/652433.

- Petren, K.; Grant, P. R.; Grant, B. R.; Keller, L. F. (2005). "Comparative landscape genetics and the adaptive radiation of Darwin's finches: the role of peripheral isolation". Molecular Ecology 14 (10): 2943–2957. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2005.02632.x.

- Pinto, Gabriel, Luke Mahler, Luke J. Harmon, and Jonathan B. Losos. "Testing the Island Effect in Adaptive Radiation: Rates and Patterns of Morphological Diversification in Caribbean and Mainland Anolis Lizards." NCBI (2008): n. pag. Web. 28 Oct. 2014.

- Rainey, P. B.; Travisano, M. (1998). "Adaptive radiation in a heterogeneous environment". Nature 394 (6688): 69–72. doi:10.1038/27900.

- Schluter, D (1995). "Adaptive radiation in sticklebacks: trade-offs in feeding performance and growth". Ecology: 82–90.

- Schluter, Dolph. The ecology of adaptive radiation. Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Seehausen, O (2004). "Hybridization and adaptive radiation". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 19 (4): 198–207. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.003.