Peptidoglicano: Diferenzas entre revisións

Sen resumo de edición |

Sen resumo de edición |

||

| Liña 6: | Liña 6: | ||

O peptidoglicano exerce un papel estrutural na célula bacteriana, dándolle forza estrutural, e protexéndoa da [[presión osmótica]] exercida polo [[citoplasma]]. Aínda que o peptidoglicanolle dá forza estrutural á parede, para a determinación da súa forma necesítanse tamén as proteínas [[MreB]] e [[RodZ]]. <ref name="pmid11544518">{{cite journal| author=van den Ent F, Amos LA, Löwe J| title=Prokaryotic origin of the actin cytoskeleton. | journal=Nature | year= 2001 | volume= 413 | issue= 6851 | pages= 39–44 | pmid=11544518 | doi=10.1038/35092500 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=11544518 }} </ref><ref name="pmid20168300">{{cite journal| author=van den Ent F, Johnson CM, Persons L, de Boer P, Löwe J| title=Bacterial actin MreB assembles in complex with cell shape protein RodZ. | journal=EMBO J | year= 2010 | volume= 29 | issue= 6 | pages= 1081–90 | pmid=20168300 | doi=10.1038/emboj.2010.9 | pmc=2845281 }} </ref> O peptidoglicano está tamén implicado na [[fisión binaria]] durante a división celular bacteriana. |

O peptidoglicano exerce un papel estrutural na célula bacteriana, dándolle forza estrutural, e protexéndoa da [[presión osmótica]] exercida polo [[citoplasma]]. Aínda que o peptidoglicanolle dá forza estrutural á parede, para a determinación da súa forma necesítanse tamén as proteínas [[MreB]] e [[RodZ]]. <ref name="pmid11544518">{{cite journal| author=van den Ent F, Amos LA, Löwe J| title=Prokaryotic origin of the actin cytoskeleton. | journal=Nature | year= 2001 | volume= 413 | issue= 6851 | pages= 39–44 | pmid=11544518 | doi=10.1038/35092500 | pmc= | url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=11544518 }} </ref><ref name="pmid20168300">{{cite journal| author=van den Ent F, Johnson CM, Persons L, de Boer P, Löwe J| title=Bacterial actin MreB assembles in complex with cell shape protein RodZ. | journal=EMBO J | year= 2010 | volume= 29 | issue= 6 | pages= 1081–90 | pmid=20168300 | doi=10.1038/emboj.2010.9 | pmc=2845281 }} </ref> O peptidoglicano está tamén implicado na [[fisión binaria]] durante a división celular bacteriana. |

||

A capa de peptidoglicano é moito máis grosa nas bacterias [[Gram-positiva]]s, nas que ten entre 20 e 80 [[nanómetro]]s de grosor, ca nas [[Gram-negativa]]s, nas que só ten entre 7 e 8 nanómetros, coa adhesión dunha [[capa S]]. O peptidoglicano constitúe arredor do 90 % do [[peso seco]] das bacterias Gram-positivas, pero só o 10% das Gram-negativas. Deste modo, a presenza de grandes cantidades de peptidoglicano é a característica principal das para caracterizar as bacterias Gram-positivas. <ref>C.Michael Hogan. 2010. [http://www.eoearth.org/article/Bacteria?topic=49480 ''Bacteria''. Encyclopedia of Earth. eds. Sidney Draggan and C.J.Cleveland, National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC]</ref> Nas bacterias Gram-positivas o peptidoglicano é importante para a adhesión a superficies e para o estereotipado. <ref name=Salton1996>{{cita libro | autor = Salton MRJ, Kim KS | título = Structure. ''In:'' Baron's Medical Microbiology ''(Barron S ''et al.'', eds.)| edición = 4th | editor = Univ of Texas Medical Branch | ano = 1996 | url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=mmed.section.289#297 | isbn=0-9631172-1-1 }}</ref> As partículas de aproximadamente 2 nanómetros poden atravesar o peptidoglicano, tanto nas Gram-positivas coma nas negativas. <ref>{{cite journal | author=Demchick PH, Koch AL | title=The permeability of the wall fabric of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis | journal=Journal of Bacteriology | date=1 February 1996| pages=768–73| volume=178 | issue=3 |url=http://jb.asm.org/cgi/reprint/178/3/768 | pmid=8550511 | pmc=177723 }}</ref> |

|||

== Estrutura == |

== Estrutura == |

||

[[ |

[[Ficheiro:Peptidoglycan en.svg|thumb|Peptidoglicano.]] |

||

The peptidoglycan layer in the bacterial cell wall is a [[crystal lattice]] structure formed from linear chains of two alternating amino [[sugar]]s, namely [[N-Acetylglucosamine|''N''-acetylglucosamine]] (GlcNAc or NAG) and [[N-Acetylmuramic acid|''N''-acetylmuramic acid]] (MurNAc or NAM). The alternating sugars are connected by a β-(1,4)-[[glycosidic bond]]. Each MurNAc is attached to a short (4- to 5-residue) [[amino acid]] chain, containing [[alanine|<small>L</small>-alanine]], [[glutamic acid|<small>D</small>-glutamic acid]], [[meso-diaminopimelic acid|''meso''-diaminopimelic acid]], and [[alanine|<small>D</small>-alanine]] in the case of ''[[Escherichia coli]]'' (a Gram-negative bacteria) or [[alanine|<small>L</small>-alanine]], [[glutamine|<small>D</small>-glutamine]], [[lysine|<small>L</small>-lysine]], and <small>D</small>-alanine with a 5-glycine interbridge between tetrapeptides in the case of ''[[Staphylococcus aureus]]'' (a Gram-positive bacteria). These amino acids, except the <small>L</small>-amino acids, do not occur in proteins and are thought to help protect against attacks by most peptidases{{Citation needed|date=November 2008}}. |

The peptidoglycan layer in the bacterial cell wall is a [[crystal lattice]] structure formed from linear chains of two alternating amino [[sugar]]s, namely [[N-Acetylglucosamine|''N''-acetylglucosamine]] (GlcNAc or NAG) and [[N-Acetylmuramic acid|''N''-acetylmuramic acid]] (MurNAc or NAM). The alternating sugars are connected by a β-(1,4)-[[glycosidic bond]]. Each MurNAc is attached to a short (4- to 5-residue) [[amino acid]] chain, containing [[alanine|<small>L</small>-alanine]], [[glutamic acid|<small>D</small>-glutamic acid]], [[meso-diaminopimelic acid|''meso''-diaminopimelic acid]], and [[alanine|<small>D</small>-alanine]] in the case of ''[[Escherichia coli]]'' (a Gram-negative bacteria) or [[alanine|<small>L</small>-alanine]], [[glutamine|<small>D</small>-glutamine]], [[lysine|<small>L</small>-lysine]], and <small>D</small>-alanine with a 5-glycine interbridge between tetrapeptides in the case of ''[[Staphylococcus aureus]]'' (a Gram-positive bacteria). These amino acids, except the <small>L</small>-amino acids, do not occur in proteins and are thought to help protect against attacks by most peptidases{{Citation needed|date=November 2008}}. |

||

Revisión como estaba o 1 de xuño de 2012 ás 17:06

Este artigo está a ser traducido ao galego por un usuario desta Wikipedia; por favor, non o edite. O usuario Miguelferig (conversa · contribucións) realizou a última edición na páxina hai 11 anos. Se o usuario non publica a tradución nun prazo de trinta días, procederase ó seu borrado rápido. |

O peptidoglicano, tamén chamado mureína, é un polímero formado por azucres e aminoácidos que forma unha capa reticular que rodea a membrana plasmática da maioría das bacterias (pero non das arqueas) e que constitúe a súa parede celular. O compoñente carbohidrato do peptidoglicano é un heteropolisacárido formado por residuos alternantes dos monosacáridos N-acetilglicosamina e ácido N-acetilmuráamico, unidos entre si por enlace glicosídico β-(1,4). As cadeas deste heteropolisacárido dispóñense paralelamente. Unido ao ácido N-acetilmurámico está o compoñente aminoacídico, que é un péptido de tres a cinco aminoácidos. Esta cadea peptídica pode establecer enlaces cruzados cos péptidos doutras cadeas do heteropolisacárido, formando unha capa reticular tridimensional. [1]

Algunhas Archaea teñen unha capa bastante similar pero de pseudopeptidoglicano ou pseudomureína, na que os residuos de azucres están unidos por enlaces glicosídicos β-(1,3) e os azucres que a forman son a N-acetilglicosamina e a ácido N-acetiltalosaminurónico. Isto explica que a parede das qrqueas sexa insensible á lisocima, que ataca ao peptidoglicano. [2]

O peptidoglicano exerce un papel estrutural na célula bacteriana, dándolle forza estrutural, e protexéndoa da presión osmótica exercida polo citoplasma. Aínda que o peptidoglicanolle dá forza estrutural á parede, para a determinación da súa forma necesítanse tamén as proteínas MreB e RodZ. [3][4] O peptidoglicano está tamén implicado na fisión binaria durante a división celular bacteriana.

A capa de peptidoglicano é moito máis grosa nas bacterias Gram-positivas, nas que ten entre 20 e 80 nanómetros de grosor, ca nas Gram-negativas, nas que só ten entre 7 e 8 nanómetros, coa adhesión dunha capa S. O peptidoglicano constitúe arredor do 90 % do peso seco das bacterias Gram-positivas, pero só o 10% das Gram-negativas. Deste modo, a presenza de grandes cantidades de peptidoglicano é a característica principal das para caracterizar as bacterias Gram-positivas. [5] Nas bacterias Gram-positivas o peptidoglicano é importante para a adhesión a superficies e para o estereotipado. [6] As partículas de aproximadamente 2 nanómetros poden atravesar o peptidoglicano, tanto nas Gram-positivas coma nas negativas. [7]

Estrutura

The peptidoglycan layer in the bacterial cell wall is a crystal lattice structure formed from linear chains of two alternating amino sugars, namely N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc or NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc or NAM). The alternating sugars are connected by a β-(1,4)-glycosidic bond. Each MurNAc is attached to a short (4- to 5-residue) amino acid chain, containing L-alanine, D-glutamic acid, meso-diaminopimelic acid, and D-alanine in the case of Escherichia coli (a Gram-negative bacteria) or L-alanine, D-glutamine, L-lysine, and D-alanine with a 5-glycine interbridge between tetrapeptides in the case of Staphylococcus aureus (a Gram-positive bacteria). These amino acids, except the L-amino acids, do not occur in proteins and are thought to help protect against attacks by most peptidases[Cómpre referencia].

Cross-linking between amino acids in different linear amino sugar chains occurs with the help of the enzyme transpeptidase and results in a 3-dimensional structure that is strong and rigid. The specific amino acid sequence and molecular structure vary with the bacterial species.[8]

-

The structure of peptidoglycan.

-

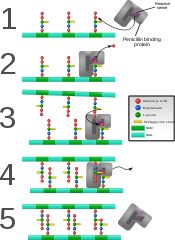

Penicillin binding protein forming cross-links in newly formed bacterial cell wall.

Inhibición por antibióticos

Some antibacterial drugs such as penicillin interfere with the production of peptidoglycan by binding to bacterial enzymes known as penicillin-binding proteins or transpeptidases.[6] Penicillin-binding proteins form the bonds between oligopeptide crosslinks in peptidoglycan. For a bacterial cell to reproduce through binary fission, more than a million peptidoglycan subunits (NAM-NAG+oligopeptide) must be attached to existing subunits.[9] Mutations in transpeptidases that lead to reduced interactions with an antibiotic are a significant source of emerging antibiotic resistance.[10]

Considered the human body's own antibiotic, lysozymes found in tears work by breaking the β-(1,4)-glycosidic bonds in peptidoglycan (see below) and thereby destroying many bacterial cells. Antibiotics such as penicillin commonly target bacterial cell wall formation (of which peptidoglycan is an important component) because animal cells do not have cell walls.

Biosíntese

The peptidoglycan monomers are synthesized in the cytosol and are then attached to a membrane carrier bactoprenol. Bactoprenol transports peptidoglycan monomers across the cell membrane where they are inserted into the existing peptidoglycan.[11]

In the first step of peptidoglycan synthesis, the glutamine, which is an amino acid, donates an amino group to a sugar, fructose 6-phosphate. This turns fructose 6-phosphate into glucosamine-6-phosphate. In step two, an acetyl group is transferred from acetyl CoA to the amino group on the glucosamine-6-phosphate creating N-acetyl-glucosamine-6-phosphate.[12] In step three of the synthesis process, the N-acetyl-glucosamine-6-phosphate is isomerized, which will change N-acetyl-glucosamine-6-phosphate to N-acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphate.[12]

In step four, the phosphate-N-acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphate, which is now a mono phosphate, attacks UTP. Uridine triphosphate, which is a pyrimidine nucleotide, has the ability to act as an energy source. When UDP is used as an energy source, it gives off an inorganic phosphate. In this particular reaction after the monophosphate has attacked the UTP, a phosphate is given off as pyrophosphate, an inorganic phosphate, and is replaced by the monophosphate, creating UDP-Nacetylglucosamine (2,4. This initial stage, is used to create the precursor for the NAG in peptidoglycan.

In step 5, some of the UDP-Nacetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) is converted to UDP-MurNAc (UDP-N acetylmuramic acid) by the addition of a lactyl group to the glucosamine. Also in this reaction, C3 hydroxyl group will remove a phosphate form the alpha carbon of phosphenol pyruvate. This creates what is called an enol derivative that will be reduced to a “lactyl moiety” by NADPH in step six.[12]

In step 7, the UDP–MurNAc is converted to UDP-MurNAC pentapeptide by the addition of five amino acids, usually including the dipeptide D-alanyl-D-alanine.[12] Each of these reactions requires the energy source ATP.[12] This is all referred to as Stage one.

Stage two is occurs in the cytoplasmic membrane. It is in the membrane where a lipid carrier called bactoprenol carries peptidoglycan precursors through the cell membrane. Bactoprenol will attack the UDP-MurNAc penta, creating a PP-MurNac penta, which is now a lipid. UDP-GlcNAc is then transported to MurNAc, creating Lipid-PP-MurNAc penta-GlcNAc, a disaccharide, also a precursor to peptidoglycan.[12] How this molecule is transported through the membrane is still not understood. However, once it is there, it is added to the growing glycan chain.[12] The next reaction is known as tranglycosylation. In the reaction, the hydroxyl group of the GlcNAc will attach to the MurNAc in the glycan, which will displace the lipid-PP from the glycan chain. The enzyme responsible for this is transglycosylase.[12] Modelo:Clear-left

Notas

- ↑ Animation of Synthesis of Peptidoglycan Layer

- ↑ Madigan, M. T., J. M. Martinko, P. V. Dunlap, and D. P. Clark. Brock biology of microorganisms. 12th ed. San Francisco, CA: Pearson/Benjamin Cummings, 2009.

- ↑ van den Ent F, Amos LA, Löwe J (2001). "Prokaryotic origin of the actin cytoskeleton.". Nature 413 (6851): 39–44. PMID 11544518. doi:10.1038/35092500.

- ↑ van den Ent F, Johnson CM, Persons L, de Boer P, Löwe J (2010). "Bacterial actin MreB assembles in complex with cell shape protein RodZ.". EMBO J 29 (6): 1081–90. PMC 2845281. PMID 20168300. doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.9.

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan. 2010. Bacteria. Encyclopedia of Earth. eds. Sidney Draggan and C.J.Cleveland, National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 Salton MRJ, Kim KS (1996). Univ of Texas Medical Branch, ed. Structure. In: Baron's Medical Microbiology (Barron S et al., eds.) (4th ed.). ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Demchick PH, Koch AL (1 February 1996). "The permeability of the wall fabric of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis". Journal of Bacteriology 178 (3): 768–73. PMC 177723. PMID 8550511.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Bauman R (2007). 2nd, ed. Microbiology with Diseases by Taxonomy. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-7679-8.

- ↑ Spratt BG (1994). "Resistance to antibiotics mediated by target alterations". Science (New York) 264 (5157): 388–93. PMID 8153626. doi:10.1126/science.8153626. Parámetro descoñecido

|month=ignorado (Axuda) - ↑ "II. THE PROKARYOTIC CELL: BACTERIA". Consultado o 1. MAY 2011.

- ↑ 12,0 12,1 12,2 12,3 12,4 12,5 12,6 12,7 White, D. (2007). The physiology and biochemistry of prokaryates (3rd ed.). NY: Oxford University Press Inc.